Independence, confederation, and foreign alliances. For months, these three elements were the talk of the Continental Congress. When Richard Henry Lee’s resolution was presented on June 7, 1776, it called for these three things, in this order:

His resolution, or more accurately, his three resolutions were adapted from those of the Virginia Convention, agreed to on May 15 : “Resolved, unanimously, That the Delegates appointed to represent this Colony in General Congress be instructed to propose to that respectable body to declare the United Colonies free and independent States, absolved from all allegiance to, or dependence upon, the Crown or Parliament of Great Britain; and that they give the assent of this Colony to such declaration, and to whatever measures may be thought proper and necessary by the Congress for forming alliances, and a Confederation of the Colonies, at such time and in the manner as to them shall seem best: Provided, That the power of forming Governments for, and the regulations of the internal concerns of each Colony, be left to the respective Colonial Legislatures.”

Minutes of the Virginia Convention, Library of Virginia

The Journals of the Continental Congress show that these three resolutions occupied the debate on Saturday, June 8 and Monday, June 10. John Hancock even let George Washington know, “we have been two Days in a Committee of the Whole deliberating on three Capital Matters, the most important in their Nature of any that have yet been before us…” On the 10th, Congress resolved, “that the consideration of the first resolution be postponed to this day, three weeks, and in the mean while, that no time be lost, in case the Congress agrees thereto, that a committee be appointed to prepare a declaration to the effect of the said first resolution.” This pushed the discussion of independence to July 1. Read more about Delegate Discussions: The Lee Resolution(s)

September 4, 2017

When the engrossed parchment copies of the Declaration of Independence and the United States Constitution were installed at the National Archives on December 15, 1952, President Harry S. Truman connected the two documents as follows:

“Everyone who holds office in the Federal Government or in the government of one of our States takes an oath to support the Constitution of the United States. I have taken such an oath many times, including two times when I took the special oath required of the President of the United States. This oath we take has a deep significance. Its simple words compress a lot of our history and a lot of our philosophy of government into one small space. In many countries men swear to be loyal to their king, or to their nation. Here we promise to uphold and defend a great document. This is because the document sets forth our idea of government. And beyond this, with the Declaration of Independence, it expresses our idea of man. We believe that man should be free. And these documents establish a system under which man can be free and set up a framework to protect and expand that freedom.”

For the majority of the history of the United States, the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution have been invoked in this way. But what about the physical connections between the Declaration and the Constitution? September 17, 2017 marks the 230th anniversary of the signing of the United States Constitution, an event both similar to and quite different from the signing of the Declaration of Independence. In this month’s research highlight, we examine the preparation and signing of these two foundational documents, and the individuals involved in both. . Read more about September Highlight: The Declaration and the Constitution

In March 2017, the Guilford Courthouse National Military Park celebrated its.

In this edition of "Presenting the Facts", we explore the 1972 movie adaptation of the musical 1776. The concept, music, and lyrics were by Sherman Edwards, and the book was written by Peter Stone. The musical opened on March 16, 1969 and closed on February 13, 1972. The movie, which was directed by Peter H. Hunt and produced by Jack L. Warner, was released in November of that year.

With the current success of Hamilton: An American Musical, the concept of a musical based on the founding generation makes complete sense. But when 1776 first opened on Broadway, it was (pardon the pun) revolutionary. Sherman Edwards was a former history teacher who merged his knowledge of early American history with his talent for songwriting to create a musical focused on the Continental Congress in the months leading up to July 4, 1776.

The libretto for 1776 includes a Historical Note by the Authors, which begins as follows: "The first question we are asked by those who have seen—or read—1776 is invariably: 'Is it true? Did it really happen that way?' The answer is: Yes." Edwards and Stone list "those elements of [the] play that have been taken, unchanged and unadorned, from documented fact," followed by dramatic changes that fall into one of five categories: "things altered, things surmised, things added, things deleted, and things rearranged." We use Edwards' descriptions of facts and fictions as our guide, adding commentary and corrections along the way. So, sit down, open up a window, and learn about what's fact and what's fiction in 1776.

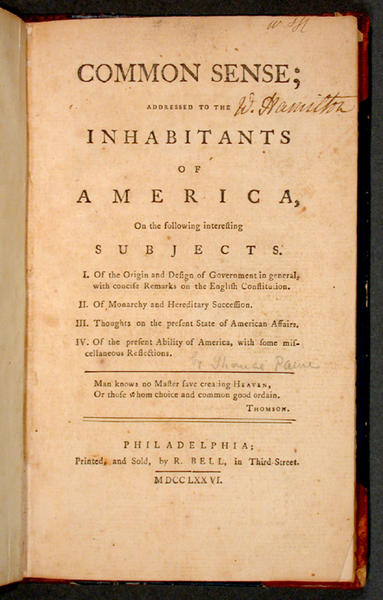

THIS day was published, and is now selling by Robert Bell, in Third-street (price two shillings) COMMON SENSE addressed to the inhabitants of America, on the following interesting SUBJECTS.

I. Of the origin and design of government in general, with concise Remarks on the English constitution.

II. Of Monarchy and Hereditary Succession.

III. Thoughts on the present state of American affairs.

IV. Of the present ability of America, with some miscellaneous reflections.

The Pennsylvania Evening Post printed the above advertisement on January 9, 1776. This pamphlet written by Thomas Paine (though the world didn't know that yet) spread like wildfire through the American colonies, with Paine claiming in his later work Rights of Man that over 100,000 copies of Common Sense had been sold. Paine and Bell's timing could not have been better — in that same issue of the Pennsylvania Evening Post, on the same page as the advertisement for Common Sense in fact, was the text of a speech King George III delivered in Parliament on October 27, 1775. A speech that expanded on the King's earlier Proclamation of Rebellion and included inflammatory remarks such as "When the happy and deluded multitude. shall become sensible of their error, I shall be ready to receive the misled with tenderness and mercy!" Enter Paine's pamphlet, which argued that "the sun never shined on a cause of greater worth" and "the last cord is now broken" .

Since it was first printed in Philadelphia, some of the first readers of Common Sense were the delegates to the Second Continental Congress. Some were thrilled by Common Sense, while others appreciated the section on American independence and dismissed the rest of it. As Steven Pincus explains in The Heart of the Declaration, "perhaps no single piece of writing did more to articulate the importance of unmaking the British Empire than Thomas Paine's Common Sense," but the plan of government described in the pamphlet "was a far cry from that envisioned by most Patriots." One delegate in particular "dreaded the Effect so popular a pamphlet might have, among the People" (any guesses who?). Find out what these soon-to-be signers of the Declaration of Independence thought about Common Sense, which signer took credit for giving the pamphlet its name, and how John Adams responded to the "Disastrous Meteor", Thomas Paine.

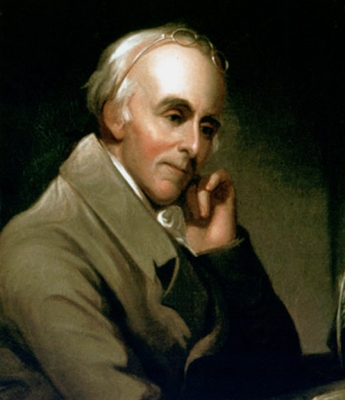

In February 1790, Dr. Benjamin Rush wrote a letter to John Adams, disparaging the histories of the American Revolution that had been written thus far: "Had I leisure, I would endeavor to rescue those characters from Oblivion, and give them the first place in the temple of liberty. What trash may we not suppose has been handed down to us from Antiquity, when we detect such errors, and prejudices in the history of events of which we have been eye witnesses, & in which we have been actors?" John Adams felt much the same, lamenting in his response written in April, "The History of our Revolution will be one continued Lye from one End to the other. The Essence of the whole will be that Dr. Franklins electrical Rod, Smote the Earth and out Spring General Washington. That Franklin electrified him with his Rod--and thence forward these two conducted all the Policy Negotiations Legislation and War . These underscored Lines contain the whole Fable Plot and Catastrophy."

In the context of this conversation, Rush informed Adams that he had written "characters of the members of Congress who subscribed the declaration of independence." These characters are a part of Rush's autobiography, Travels Through Life or Sundry Incidents in the Life of Dr. Benjamin Rush, which was completed around 1800. The autobiography was intended for Rush's children and was later published, but in 1790, Rush offered Adams a glimpse. Read more about Delegate Discussions: Benjamin Rush's Characters

Last month, we debunked John Trumbull's Declaration of Independence. Often assumed to depict the signing of the Declaration of Independence, Trumbull actually chose to immortalize the moment when the Committee of Five presented their draft of the Declaration to John Hancock and the Continental Congress.

So, when was the Declaration of Independence signed?

Spoiler: NOT ON JULY 4TH. *

*Most likely

Here is everything we know about the signing of the Declaration of Independence, the signatures, and why those signatures matter.

The Journals of the Continental Congress provide very few details about the events in late June and early July 1776. Thomas Jefferson kept notes on the proceedings, but for the rest of their lives he and other delegates tried (often in vain) to remember exactly what happened in those days. Our best glimpse into Independence Hall, and especially into the minds and emotions of the delegates to Continental Congress, is through the letters they sent to family, friends, and colleagues. Here is a glimpse, spanning from June 28th through July 9th, of what the delegates were writing while in Philadelphia, and what they were feeling as they answered the "Great Question" of American independence. For the full-length letters, see the Library of Congress' digital transcriptions of Letters of Delegates to Congress. . Read more about Delegate Discussions: Answering the Great Question

In previews last year, the award-winning musical Hamilton included a short song at the top of Act 2 (between Thomas Jefferson's "What'd I Miss?" and "Cabinet Battle #1") that was cut before the musical moved to Broadway. The number was called "No John Trumbull", and antagonist/narrator Aaron Burr sang the following lines:

You ever see a painting by John Trumbull?

Founding Fathers in a line, looking all humble

Patiently waiting to sign a declaration, to start a nation

No sign of disagreement, not one grumble

The reality is messier and richer, kids

The reality is not a pretty picture, kids

Every cabinet meeting is a full-on rumble

What you 'bout to see is no John Trumbull

- Hamilton: An American Musical, Lyrics by Lin-Manuel Miranda

The founding of the United States of America was certainly not the "pretty picture" John Trumbull's Declaration of Independence leads the viewer to believe. More specifically, the events surrounding the Declaration of Independence had very little resemblance to this now famous painting. . Read more about Unsullied by Falsehood: No John Trumbull

This is the first blog post in a new series called "Delegate Discussions", highlighting correspondence between delegates to the Continental Congress on issues related to the Declaration of Independence.

In 1819, a document was widely published for the first time. It caused cries of plagiarism to ring out through the country. It caused John Adams to call Thomas Paine's Common Sense a "crapulous mass". It caused Thomas Jefferson to profess unbelief in such an "apocryphal gospel".

The document was the Mecklenburg Declaration, issued on May 20, 1775 and strikingly similar to the United States Declaration of Independence of July 4, 1776, but from a full year earlier. The legitimacy of the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence is still contested today. In this blog, we leave aside the question of its authenticity to focus on Jefferson and Adams' reactions to the revelation of this document. Enjoy a thoroughly entertaining conversation between two Founding Fathers in their twilight years (76 and 84, respectively), confounded and disgruntled by a document from North Carolina. . Read more about Delegate Discussions: The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence